|

Technically, it was 20 years ago yesterday.

https://deadspin.com/twenty-years-ago-bobby-valentine-snuck-back-into-the-d-1833891674

This is an excerpt from Matthew Callan's book Yells For Ourselves: A Story Of New York City And The New York Mets At The Dawn Of The New Millennium.

The day of June 9, 1999, which was the day Bobby Valentine wrote a whole paragraph in his obituary, is strange even by his own standards. It begins with a Shea clubhouse shouting match with Newsday reporter Marty Noble, who is upset over Valentine's accusation that the newsman hasn't spoken to him in over a year. Shortly thereafter, rookie sensation Benny Agbayani, up in the majors for less than a month and hitting homers with Ruthian frequency, suffers a freak injury during batting practice when he tips a ball into his right eye. Disgruntled outfielder Bobby Bonilla, though recently restored from the disabled list, is unavailable, even if Valentine won't (or can't) say why. Signs point to the front office having ordered a Bonilla benching, but general manager Steve Phillips has no comment, and Bonilla—never inclined to make a reporter's job easy—tells the scribes he has nothing to say and makes good on his word.

Adding to the evening's odd vibe is the presence of Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, in town to visit the United Nations. Chavez throws out the ceremonial first pitch while draped in a billowy warm-up jacket adorned with the colors of his nation's flag and wearing a full Mets uniform, including pinstriped pants. In deference to this guest, the Venezuelan national anthem is played prior to the start of the game, in addition to the standard “Star-Spangled Banner†and the “O Canada†necessitated by the visiting Toronto Blue Jays.

https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-media/image/upload/s--7kyNdoBi--/c_scale,dpr_2.0,f_auto,fl_progressive,q_80,w_800/wjyu3uh1hexilq1fijhd.jpg> https://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-media/image/upload/s--7kyNdoBi--/c_scale,dpr_2.0,f_auto,fl_progressive,q_80,w_800/wjyu3uh1hexilq1fijhd.jpg>

David Wells takes the mound for Toronto to make his first start in New York since the Yankees dealt him northward for Roger Clemens. Shea hosts many Yankees fans who have no qualms about cheering for a divisional rival at the expense of the Mets. Boomer's return to the Big Apple coincides with his birthday, and a postgame shindig awaits him at trendy Soho nightclub Veruka. Club owner Noel Ashman patrols Shea's Diamond Club throughout the game, checking in with his doorman via cell phone to decree who shall be permitted to enter.

Wells looks like a man ready to celebrate as he mows down the Mets' batting order with little effort through the first eight innings. A complete game is a seeming formality until the Mets rally to tie the score in the ninth against Wells and Toronto's bullpen. A frustrating extra-inning slog follows. Shea's giant right-field scoreboard flashes periodic updates from game five of the NBA Eastern Conference finals, which ends with the Knicks triumphant over the Indiana Pacers. The game plods on.

In the top of the twelfth inning, when Mike Piazza appears to have thrown out a would-be base stealer, the umpire signals that Piazza interfered with the batter. Bobby Valentine storms out of the dugout to make his displeasure known and is ejected for his insolence. He should not have been in the dugout to witness the Mets pull out a victory, and a series sweep, by means of a bloop RBI single from Rey Ordóñez in the bottom of the fourteenth. And indeed Valentine is not present when all this happens, at least not entirely, or officially.

No one will ever know why Valentine does what he does next, and in the end, his act is so ridiculous that assigning reason to it is all but pointless. Much the same could be said of what he and the Mets did in the agonizing eleven days that preceded this one.

Turn back the calendar to May 28. The Mets have the bases loaded in the ninth inning, and are trailing by one run and down to their last out against the visiting Diamondbacks. A pitch that should go for ball four and force in the tying run is instead called a strike. They proceed to lose by the excruciating score of 2–1.

Thus begins a week of tough luck, near misses, and bad blood, a dark period when no calls or bounces go the Mets' way. Game two against the Diamondbacks is a three-hour, forty-minute trial in which their bullpen is roughed up and they again lose by one run. The next day, a sizeable crowd arrives at Shea Stadium for a Sunday matinee that also happens to be Beanie Baby Day (an important occasion in the year 1999), but few remain to see the conclusion of the 10–1 drubbing.

When the Reds come to Queens on May 31 and take the opener of their three-game series, Bobby Valentine chooses to accentuate the positive. He declares that Al Leiter—making his first start in seven days due to a persistent knee issue—was “four or five pitches away from a complete game shutout.†Those four or five pitches presumably include both the two-run homer by Pokey Reese and a 423-foot bomb off the bat of Greg Vaughn that sealed another Mets loss. On June 1, they are shut out 4–0 by Pete Harnisch, an ex-Met who, upon his release in 1997, couldn't wait to call WFAN and tell the world that no one in the Shea clubhouse respected Bobby Valentine.

In a back-and-forth series finale on June 2, the Mets come from behind in the late innings and carry a one-run lead into the top of the ninth. Two quick outs from closer John Franco put the home team in excellent position to grab a morale-boosting win. Then in a flash, a walk, an infield hit, a double steal, and a single up the middle. Franco spins around like a top, watching the ball skip into the outfield as the tying and go-ahead runs score behind his back. The Mets fall yet again, 8–7. Thus concludes a miserable 0-6 homestand.

With the Mets' season hanging in the balance, the pitchforks emerge from the mob, and most point their sharpened tines at Bobby Valentine. Murray Chass of the Times, long a Valentine nemesis, ascribes the Mets' slide to their manager because “Valentine has more people in baseball pulling against him than any other individual.â€

What the Mets could use is a low-stress road series far away from New York's glaring spotlight. What the Mets will get instead is the exact opposite: the Subway Series.

In the opener in the Bronx on June 4, Rey Ordóñez knocks a double to tie the score in the top of the sixth, but the Mets are prevented from sending the go-ahead run home when a spectator leans over one of Yankee Stadium's low field-level walls and interferes with the ball. “Who knows what would have happened had the Mets gotten both runs?†Bill Madden wonders in the Daily News, before coming to the conclusion, “They probably would have found some other way to lose the game.â€

The way they do find to lose is a Rickey Henderson miscue that allows the Yankees to retake the lead. In the ninth, Edgardo Alfonzo hits a long fly ball to right, tantalizingly close to a two-run homer, but the Mets lead the league in near misses these days. The ball settles into Paul O'Neill's glove a few inches on the wrong side of the wall. The Mets lose again, 4–3, their seventh consecutive defeat.

With all other tactics exhausted, Valentine opts for cockeyed optimism. “I can't be any more proud of a team,†he says in the wake of yet another defeat. “We're playing a good brand of baseball . . . Other than a victory, there's nothing negative I can say about my guys.†Other than victory . . . What a thing for a manager to say, and to say it at Yankee Stadium, where there is nothing other than victory.

Rumors begin to swirl that Valentine's days as manager are numbered. General manager Steve Phillips swears Valentine is doing a “good job,†but not every Met agrees. During an interview with John Franco, WFAN's Chris “Mad Dog†Russo shares his belief that the Mets don't give their all for Valentine. Franco coyly responds, “You may have something there.â€

There is no better demonstration of the Mets' recent luck than the moment in the top of the second of Subway Series game two, when Rey Ordóñez hits a sharp grounder right back to pitcher Orlando Hernández, smacking the ball so hard it wedges between the fingers of his glove. Unable to dislodge the ball, Hernández flings his whole glove toward first base overhand to record an unusual force out. If ever the baseball gods sent the message “This is not your day,†surely this was it. The Mets fall yet again, 6–3.

Before the game, Steve Phillips is blindsided by published rumors he is about to fire Mets pitching coach Bob Apodaca, whose close relationship with Bobby Valentine means a lot less now than it once did. Phillips neither confirms nor denies such rumors while backpedaling from the tepid “good job†endorsement of Valentine he'd muttered a day ago. When asked if Valentine's status is as shaky as that of his pitching coach, Phillips says tersely, “Draw your own conclusions.â€

Later that evening, Phillips addresses the press via conference call to inform them he has dismissed half of the Mets' coaching staff. Apodaca gets the axe as expected, but so do two other coaches who are close confidants of Bobby Valentine. The trio formed Valentine's brain trust in the Mets' clubhouse. Now, all are gone. The general manager insists the outcome of the Subway Series had no bearing on the move. He offers no explanation as to why this decision was announced in the dead of night on a Saturday. He also denies the firings are a backhanded attempt to force the manager to quit, but it is widely assumed that the Mets see Bobby Valentine out on a ledge and are giving him multiple reasons to jump.

If this is in fact the Mets' intent, Valentine refuses to play his part. He insists his fired underlings insisted he stay on and fight rather than quit, though this contention is regarded with all the skepticism it deserves. Shovel in hand, Murray Chass pens a column entitled “To Valentine, It Seems, Loyalty Has Its Limits.†What kind of person would continue on like this, Chass argues, when his bosses are telegraphing that they want him gone?

The stage is set for a cringe-inducing press conference prior to the Subway Series finale on June 6. Steve Phillips does most of the talking, defending his actions in clipped, measured phrases, expressing remorse that, sigh, it has come to this. Bobby Valentine sits at his side, looking like a hyperactive child forced to squirm through Sunday mass, his eyes darting in every direction. He bites his knuckles throughout the grotesque charade, as if afraid his mouth might betray him if it isn't filled with something.

When asked if he's “lost†the team, Valentine responds, “None of my power is gone. I still have total control over things I've always had control over.†In truth, at this point, Valentine has control over nothing but words, so he forms them into a cudgel and wields them on himself. The Mets have played fifty-five games to this point in the season. In his opinion, the Mets have the talent and ability to win forty of the next fifty-five games they play—and if they don't, he deserves to be fired.

A few outlets interpret this as some brilliant three-dimensional chess move. But most report the manager's words with little comment. Given the Mets' struggles, forty out of fifty-five sounds like the ranting of a madman, or of a man who begs to be fired because he's too proud to quit. The Post compares Valentine's prediction to putting a gun to his own head and asking the front office to pull the trigger.

The Mets desperately need to salvage a victory in the Subway Series finale but will have to do so against Roger Clemens, winner of twenty decisions in a row, an American League record. The Rocket hasn't been perfect this season, but the potent Yankee offense has bailed him out more than once, proving it is often better to be lucky than good. The Mets will counter with Al Leiter, who—despite his rep as the team's ace—has been neither lucky nor good so far in 1999.

This confluence of events seems laboratory engineered to end the Mets' season before the All-Star break, which makes what happens during the game even more remarkable. The Mets load the bases against Clemens in the top of the second, setting up back-to-back two-run hits, all while the unnerved fireballer stares in at the umpire and stalks the mound when close calls are deemed balls instead of strikes. The Rocket is even more perturbed in the third inning by a two-run homer by Mike Piazza, a monster shot that lands in a narrow corner of the Yankees' bullpen.

Moments later, Clemens departs with one of the ugliest pitching lines of his career: 2 2/3 innings, eight hits, seven runs, all earned. With the home team trailing by seven runs, Bronx Bombers fans head for the exits and hubristic Mets fans, starved for anything to cheer, taunt the ones who remain—including New York's No. 1 Yankee fan, Mayor Rudy Giuliani, who hears it from orange-and-blue partisans for the rest of the evening.

As amazing as the Mets' sudden bout of clutch hitting is, Al Leiter's performance is even more so. The Mets' reputed ace finally pitches like one, allowing only one run on four hits in seven innings of work. The visitors sail to a stress-free 7–2 victory. With no need to excuse another mediocre outing, Leiter quips, “I'm so relieved just so I don't have to answer your questions of why I'm so shitty.â€

The Mets follow their win over the Yankees by taking the first two games of a series against Toronto at Shea. But a modest three-game winning streak is not sufficient to end the Bobby Valentine Death Watch. Newspapers urge the team to cut its losses and ditch Valentine for the good of everyone involved. Valentine's survival depends on restoring some sense of normalcy in the Shea clubhouse, but as Jack Curry points out in the New York Times, “Exactly what is normal for the Mets is still uncertain.â€

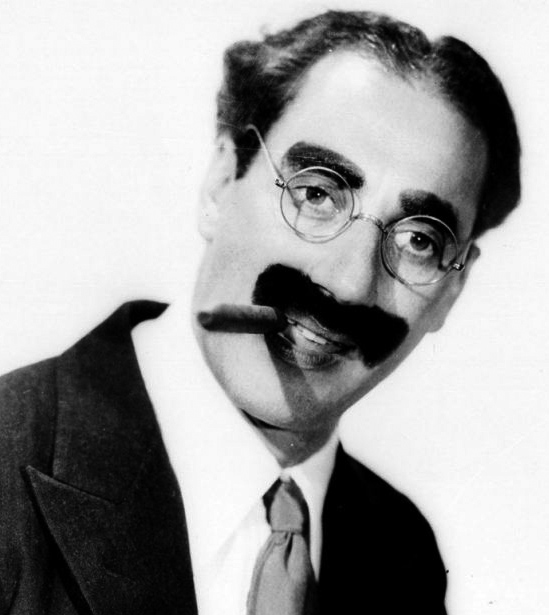

Moments after Valentine is given his early exit on the evening of June 9, the television cameras spy a lurker in the Mets' dugout. In the strictest sense, this man is not in the dugout but on the top step connecting the dugout to the clubhouse tunnel. On his head, a black baseball cap with an indecipherable logo. He wears a Mets T-shirt that has the cheap look of a bootleg. His eyes are obscured by a large pair of aviator sunglasses. Below his nose, a laughably fake mustache is painted on with eye black. It is the kind of “disguise†a person would wear not to go undetected, but to be noticed.

The lurker's arms are folded. He rocks side to side, so strenuously trying not to be seen that no one can fail to miss him. The players on the bench do everything in their power to not look at him, which only serves to draw more attention his way. The mystery man in the ridiculous getup remains silent, for his appearance says everything. Isn't this supposed to be fun? he says without speaking a word. Isn't this supposed to be a game?

For those watching live, he seems to hover there forever. But only a few moments pass before he is gone. |

|